By John Saulnier, FFB Editorial Director

Now is a good time to take a moment to salute the father of the frozen food industry, Clarence Birdseye, who would have been 130 years old on December 9. It was his vision that charted the future, and his entrepreneurial energy that laid the foundation for what would become an international revolution in food preservation, production and distribution.

Now is a good time to take a moment to salute the father of the frozen food industry, Clarence Birdseye, who would have been 130 years old on December 9. It was his vision that charted the future, and his entrepreneurial energy that laid the foundation for what would become an international revolution in food preservation, production and distribution.

So, why not thaw out a frozen cake, adorn it with candles, light them, raise a glass of bubbly and sing a “Happy Birthday” tribute? Bottoms up to the naturalist, trapper, fox breeder, fur trader, engineer, inventor, entrepreneur and college dropout who forever changed the way people eat. The commercialization of his dream led to the creation of jobs for millions of people and has fed billions of mouths around the world.

Some folks in the United Kingdom might celebrate the occasion by biting into a Birds Eye brand Chocolate Arctic Roll featuring triple choc ice cream rippled and coated with chocolate flavored sauce wrapped in sponge cake. Others may prefer to indulge in the original raspberry recipe.

Some folks in the United Kingdom might celebrate the occasion by biting into a Birds Eye brand Chocolate Arctic Roll featuring triple choc ice cream rippled and coated with chocolate flavored sauce wrapped in sponge cake. Others may prefer to indulge in the original raspberry recipe.

Brooklyn, New York-born Clarence Birdseye, who spent much of his adult life northeast of Boston in the Gloucester, Massachusetts fishing harbor town on the North Atlantic, would perhaps be marking the moment with a festive meal of previously frozen haddock fillets, along with a side dish of peas or spinach, followed by a bowl of cherries or loganberries for dessert, as these were among the initial retail products launched under the Birdseye Frosted Food brand in 1930.

The genesis of Birdseye’s industrial quick freezing idea that germinated into the invention of the “Quick Freeze Machine” dates back to 1912. That’s when he ventured into the subarctic and polar regions of Labrador as a fur trader after service as a naturalist in New Mexico and Arizona, followed by a tour of duty with the US Biological Survey in the Bitterroot Mountains of westernmost Montana. He spent several years in Labrador, traveling by dogsled to buy and collect furs and pelts to sell to buyers in Europe and the United States.

More than a century ago, the eureka moment came when Birdseye witnessed the suspended animation of trout freezing almost instantaneously after being pulled out of water into extremely cold and windy -30° to -50°F winter air temperatures. It happened so rapidly there was no time for large ice crystals to form that would damage the cellular structure of the landed fish. This natural quick freezing preservation process locked in freshness to be conveniently enjoyed by consumers later. Upon thawing, no drip loss or mushiness resulted. After cooking, it served up with robust flavor, natural texture and color, and full nutritional value.

“When I went to Labrador I knew nothing of the virtues of quick freezing. I couldn’t, in fact, have told a refrigerator compressor from a condenser. But that first winter I saw natives catching fish in fifty below zero weather, which froze stiff as soon as they were taken out of the water. Months later when they were thawed out, some of these fish were still alive,” Birdseye recorded in a journal he updated daily during the expedition.

“When I went to Labrador I knew nothing of the virtues of quick freezing. I couldn’t, in fact, have told a refrigerator compressor from a condenser. But that first winter I saw natives catching fish in fifty below zero weather, which froze stiff as soon as they were taken out of the water. Months later when they were thawed out, some of these fish were still alive,” Birdseye recorded in a journal he updated daily during the expedition.

The adventurous entrepreneur spent several years in Labrador before returning to warmer climes and times in 1917 to join the US Fisheries Association in Washington, DC. He moved on in 1922, intent on applying the natural quick freezing knowledge gleaned in Labrador to perfect a mechanical system for flash-freezing fish, red meat, poultry and vegetables under high pressure.

It took a great deal of intensive study and experimentation, interrupted with disappointments along the way, to get the project off the ground, chronicled E.W. Williams in Frozen Foods: Biography of an Industry. The history reference book points out that while Birdseye did not invent the freezing process, and was not the first person to freeze food commercially, the visionary’s pioneering efforts gave birth to the multi-billion dollar business to come. Prior to his technical breakthrough, slow freezing “cold pack” strawberries and other fruits had been ongoing since 1908 in the northwestern Unites States. Well before then, in 1876, frozen meat packed in ice and salt was shipped from the US to importers in England.

In 1923, with $20,000 in seed money, Birdseye formed the first commercial quick freezing company in New York. By 1924 some $60,000 in funding from the issuance of stock was dedicated to the venture, and a factory doing business as General Seafoods Corp. was established in Gloucester.

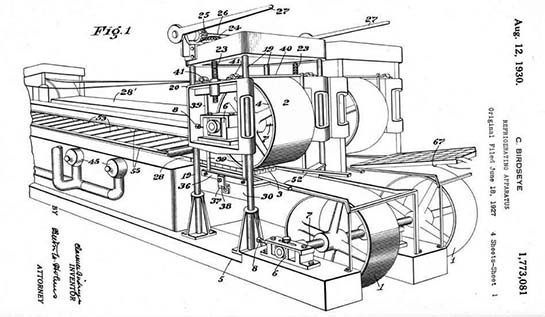

In 1926 he developed, with the assistance of Joseph Guinane, the original belt froster machine that preceded the multiple plate freezer. A year later he applied for a patent for an advanced double belt freezer, in which cold brine-chilled stainless steel belts conveying packaged fish in waxed cardboard cartons rapidly froze the payload at -13°F. This invention, far superior to the Ottoson brine freezer as well as indirect and direct refrigerant contact freezers already in use, was the catalyst for today’s global frozen food industry.

E.W. Williams, who reported that industrialist Henry Ford was attracted to Birdseye’s idea and made overtures about financing freezer production that came to naught, quoted the architect of today’s global frozen food industry as modestly saying: “My contribution was to take Eskimo knowledge and the scientists’ theories and adapt them to quantity production.”

On another occasion, the entrepreneur remarked: “To be perfectly honest, I am best described as just a guy with a very large bump of curiosity and a gambling instinct.”

His gamble on the future of frozen foods paid off big time, making him a multi-millionaire in an era when a million dollars had much more buying power than today.

“Quick freezing was conceived, born and nourished on a strange combination of ingenuity, stick-to-itiveness, sweat and good luck,” remarked Birdseye.

Williams, who launched the frozen food industry’s first trade publication in 1938 and had already been writing about the then high-tech business since 1935, reported on many of Birdseye’s achievements for decades. Indeed, the publisher enlisted him as an editorial advisor to Quick Frozen Foods magazine, a position held until his death in 1956.

Interestingly, part of the 20th Anniversary Section of the international edition of Quick Frozen Foods (QFFI), published in October of 1979, drew from a book entitled Heiress, authored by William Wright, to illuminate a chance occurrence that reportedly proved to be positively pivotal for the then fledgling frozen food business.

As the legendary story goes, Marjorie Merriweather Post, daughter of the founder of the Postum Cereal Company who became its owner upon his death in 1914, was served a delicious goose dinner while yachting off the New England coast during the summer of 1925. Impressed with the quality, she asked the chef about the bird’s origin and was astonished when told that it was sourced from a Gloucester company that had developed a new way of preserving foods.

Post, who at the time was married to Postum’s then Chairman E.F. Hutton, made arrangements to meet Clarence Birdseye, and learned that his startup enterprise was floundering. She sensed a good business opportunity in need of capital investment to finance the fledgling prepared frozen foods future.

“Before frozen foods could become widespread, not only would households have to purchase a freezer, which was an expensive piece of equipment then, but so would thousands of small independent grocers who sold food in those pre-supermarket days,” explained Williams. “But finally they (Postum) decided to buy Birdseye’s company. It was not doing well, and Clarence Birdseye named a figure of $2 million. But the board of directors reached the decision that frozen food would never catch on. However, four years later they had to pay $22 million. Later the Postsum companies were merged into the General Foods Corp., which controlled the Birds Eye name in the Western Hemisphere.”

“Before frozen foods could become widespread, not only would households have to purchase a freezer, which was an expensive piece of equipment then, but so would thousands of small independent grocers who sold food in those pre-supermarket days,” explained Williams. “But finally they (Postum) decided to buy Birdseye’s company. It was not doing well, and Clarence Birdseye named a figure of $2 million. But the board of directors reached the decision that frozen food would never catch on. However, four years later they had to pay $22 million. Later the Postsum companies were merged into the General Foods Corp., which controlled the Birds Eye name in the Western Hemisphere.”

The price paid had increased considerably, it has been speculated, because the sale included rights to certain patents Birdseye had obtained. Goldman Sachs was involved in the 1929 deal, consummated during the year of the stock market crash on Wall Street that heralded the Great Recession.

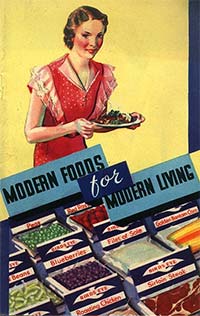

Birdseye continued to work with the company as a consultant, primarily promoting the brand and concentrating on the further development of frozen food technology. In 1930 products were test-marketed in 18 retail stores, including Davidson’s Food Market in Springfield, Massachusetts, to gauge consumer acceptance. The line consisted of 26 items including fish fillets, meat, blue point oysters, spinach, peas, and an assortment of fruits and berries. Shoppers embraced the offerings and a new way of dining at home was successfully launched.

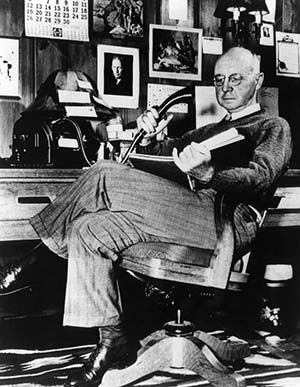

Mark Kurlansky, who published a biography in 2012 entitled Birdseye: the Adventures of a Curious Man, credits the founder of the frozen food industry with much more than inventing a machine capable of freezing food in a way that prevented damage to tissue and cellular structure. The author cited his genius in packaging and refrigerated transportation fields as well.

“If you get really small crystals the ice doesn’t deform the tissue, which was the first important thing,” he told Smithsonian.com. “But then he had to figure out a way to package it so it could be frozen in packages that were of saleable size that people in the stores could deal with, and thus did a lot of experimenting with packaging and packaging material. He actually got the DuPont Company to invent cellophane for cellophane wrappers. Then there were all these things like transportation, getting trucking companies and trains to have freezer cars and getting stores to carry freezers. There was absolutely no infrastructure for frozen food. He had to do all of that and it took more than a decade.”

Today the frozen food trade in the United States alone generates $56 billion in annual receipts and provides gainful employment for upwards of 670,000 people, according to the American Frozen Food Institute. Globally, the sector is reportedly on course to surpass $306 billion in value by 2020.

Meanwhile, the Birds Eye brand is stronger than ever. Parsippany, New Jersey-based Pinnacle Foods owns the label in the USA. Largely vegetable-oriented, it generated net sales of $343.8 million in the fourth quarter of 2015. EBIT for the Birds Eye Frozen segment increased approximately 44% to $78.3 million during that period.

In the United Kingdom the Birds Eye brand, launched by Unilever in 1943 and sold to the Permira private equity firm in 2006, was acquired in an EUR 2.6 billion (£1.9 billion) purchase made by Nomad Foods in April of 2015.

In the United Kingdom the Birds Eye brand, launched by Unilever in 1943 and sold to the Permira private equity firm in 2006, was acquired in an EUR 2.6 billion (£1.9 billion) purchase made by Nomad Foods in April of 2015.

The popular Birds Eye range in Australia and New Zealand, which features retail packs containing everything from frozen vegetables and potatoes to fish and snack foods, is a proprietary brand produced and marketed by Simplot.

The inventive Clarence Birdseye, described by Kurlansky as “a nineteenth century foodie in reverse, who ate wild local food and artisanally made products, the food of family farms, but who dreamed of making food industrial,” obtained nearly 300 patents during his highly productive lifetime of 69 years. They ranged from an electric fishing reel and recoilless harpoon gun to place identification markers on whales, to infrared heat lamps and reflecting light bulbs. The frozen food guru even developed an efficient system for dehydrating foods.

If he were to come back today, writes Kurlansky, Birdseye would see, as predicted, a truly international industry prospering in “a world in which food transcends geography and climate: any food is available anywhere at any time of year.”