By John Saulnier, FrozenFoodsBiz Editorial Director

After “Pleasing Families Since 1921” (as emblazoned on product packaging), the Eskimo Pie ice cream brand name and caricature of a young lad attired in cold weather clothing is destined to melt away as the name and logo are deemed offensive by segments of indigenous peoples originating from the circumpolar regions of North America and social activists from around the planet. The issue has been heating up since at least 2009, when a Canadian Inuit woman complained that the product name insulted her heritage.

According to Wikipedia, the term Eskimo comes from the Innu-aimun (Montagnais) word ayas̆kimew meaning “a person who laces a snowshoe.” Merriam-Webster says the perceived offensiveness of the word Eskimo “stems partly from a now-discredited belief that it was originally a pejorative term meaning ‘eater of raw flesh,’ but perhaps more significantly from its being a word imposed on aboriginal peoples by outsiders.”

Last week Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream, the maker of Eskimo Pie chocolate-covered vanilla ice cream sticks in the United States, announced that it had been contemplating renaming the popular treat for some time. Now, the time for rebranding has arrived.

“We are committed to being a part of the solution on racial equality, and recognize the term is derogatory. This move is part of a larger review to ensure our company and brands reflect our people values,” said the company’s head of marketing in public statement.

The proclamation was made in the wake of massive demonstrations and protests against racial injustice and police brutality that escalated into rioting, looting, arson and other acts of vandalism and civil unrest in many American cities following the deadly asphyxiation of a handcuffed black man, 46-year-old George Floyd, at the knee of a white police officer in Minneapolis on May 25. Other food companies, both before and after Mr. Floyd’s killing, have moved to purge controversial images and brand names associated with racial stereotyping from their product lines.

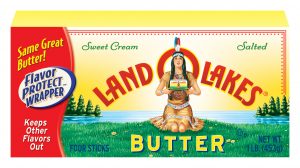

In April the Arden Hills, Minnesota-headquartered Land O’Lakes dairy cooperative removed the iconic portrait of a Native American Indian maiden that had been featured on packaging containing butter, cheese and other dairy products since 1928.

The Arthur C. Hanson illustration of kneeling Mia in a buckskin dress and feather headdress holding Land O’Lakes butter along the picturesque banks of a blue lake first appeared in 1928. The artwork was redesigned during the 1950s by Patrick DesJarlait, a member of the Native American Ojibwe tribe.

“It was a source of pride for people to have a Native artist doing that kind of work,” said Patrick’s son Robert DesJarlait, who is also an artist. “He was breaking a lot of barriers . . .Back in the 50s, nobody even thought about stereotypical imagery. Today it’s a stereotype, but it’s also a source of cultural pride. It’s a paradox in that way.”

Meanwhile, on June 17, PepsiCo subsidiary Quaker Oats signaled that the retirement of Aunt Jemima from an extensive line of products – which in addition to syrup includes frozen breakfast items such as waffles, pancakes, french toast, and scrambled eggs and bacon meals – is close at hand. All traces of the brand are likely to be gone with the wind before the end of the year.

“We recognize Aunt Jemima’s origins are based on a racial stereotype. As we work to make progress toward racial equality through several initiatives, we also must take a hard look at our portfolio of brands and ensure they reflect our values and meet our customers’ expectations,” said Kristin Kroepfl, Quaker Foods North America’s vice president and chief marketing officer.

The image of “Mammy” archetype Aunt Jemima has evolved numerous times over more than a century. The brand name was taken from an 1875 minstrel show song called “Old Aunt Jemima.” The original logo, which dates back to 1889 and has been associated with ready-made pancake batter mix ever since, was modeled on the likeness of a black woman named Nancy Green, who was a storyteller, cook, missionary worker, anti-poverty activist, brand promoter and freed slave. It was registered as a trademark in 1937, and licensed to Aurora Foods in 1996 for use as a frozen breakfast product label.

The problematic image harkens back to the antebellum plantation slave era in the south, according to Riché Richardson, an associate professor of African American literature in the Africana Studies & Research Center at Cornell University, who for many years has called for its withdrawal from the marketplace. In a 2015 article in The New York Times entitled “Can We Please, Finally, Get Rid of Aunt Jemima?” she criticized Quaker Oats for perpetuating racist symbolism on grocery store shelves.

“It is about time for there to be some honest conversation about what is at stake in continuing to market products, even nowadays, under names such as Aunt Jemima,” she wrote.

Last Wednesday, while interviewed on NBC’s Today television show, Richardson commented: “Aunt Jemima is that kind of stereotype that is premised on this idea of black inferiority and otherness. It is urgent to expunge public spaces of a lot of these symbols that for some people are triggering and represent terror and abuse.”

While removing the iconic brand name and character’s facial features from packaging will please those who believe it reinforces racial stereotypes, not to be counted among them are offspring of a Texan who once portrayed Aunt Jemima in marketing promotions.

The KLTV news station in the Lone Star State reported over the weekend that descendents of a woman who portrayed Aunt Jemima in marketing campaigns oppose the rebranding and have contacted Quaker Oats to reverse its decision.

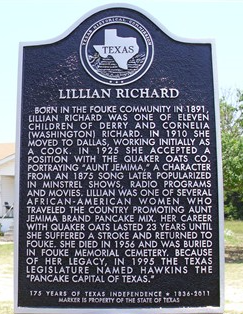

Vera Harris told KLTA that the family takes pride in Quaker Oats hiring her second cousin, Lillian Richard, who worked as brand representative for the company for 23 years and was regarded as an inspiration, not a racist stereotype, in local African-American community.

“She was considered a hero in Hawkins [her hometown, known as The Pancake Capital of Texas, where a historical marker stands in her honor], and we are proud of that. We do not want that history erased,” said Harris. “She made an honest living out of it touring around Texas” at a time when there “wasn’t a lot of jobs, especially for black women.”

Harris added: “I wish we would take a breath and not just get rid of everything, because good or bad, it is our history. Removing that wipes away a part of me — a part of each of us.”

A great-grandson of Anna Short Harrington, another person who portrayed Aunt Jemima following the death of Nancy Green and whose likeness has been replicated on packaging, has also appealed to Quaker to reconsider its decision.

“This is an injustice for me and my family. This is part of my history, sir,” Marine Corps veteran Larnell Evans Sr., told Patch.com. “The racism they talk about, using images from slavery, that comes from the other side – white people. It hurts to know that Quaker Foods’ answer to current events in America is to erase my great-grandmother’s history…“How do you think I feel as a black man sitting here telling you about my family history they’re trying to erase?”

Six years ago Evans and D.W. Hunter, also a great-grandson of Harrington, filed an unsuccessful class action lawsuit in the US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois seeking an “equitable fair share of royalties” from PepsiCo and its related subsidiaries on behalf of all of Harrington’s great-grandchildren.

Last week PepsiCo pledged $437.5 million in donations to address inequality and create opportunity for black communities and increase black representation within its ranks. Perhaps the multinational food and beverage corporation – which rang up sales of over $68 billion and generated a gross profit of more than $37 billion during the 12-month period ending on March 31, 2020 – will see fit to do the right thing by channeling a chunk of the $25 million it has earmarked for college scholarship funds to descendants of Anna Short Harrington and Lillian Richard families.