The United Kingdom stands to lose more than the European Union if a tariff is imposed on EU-UK seafood trade following the Brexit transition period, according to Beyhan de Jong, associate analyst for animal protein at Rabobank’s RaboResearch division in the Netherlands.

“While the transition agreement is expected to ensure free trade through to the end of 2020, tariffs could be introduced between the EU and the UK from 2021 onwards, depending on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations. Imposition of a tariff would hinder the UK’s seafood trade flows more than those of the EU,” she wrote in a recent post at the Rabobank website.

“While the transition agreement is expected to ensure free trade through to the end of 2020, tariffs could be introduced between the EU and the UK from 2021 onwards, depending on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations. Imposition of a tariff would hinder the UK’s seafood trade flows more than those of the EU,” she wrote in a recent post at the Rabobank website.

Based in Utrecht and holding an MSc and a PhD degree in agricultural economics from the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, Germany, Ms. De Jong’s analysis is as follows:

The UK exports most of its seafood catch, and what is consumed in the domestic market is mainly imported. Mackerel, langoustine and scallops are the top three species caught in British waters by British vessels, but they don’t have a market in the UK. These species are exported, predominantly to the EU. On the other hand, cod, haddock and pollock, as well as shrimp and prawns, are the species favored most by British consumers – yet they are largely imported. Salmon is quite different. Two-thirds of the salmon produced in the UK is exported – some 105,000 tons – while salmon imports are about half the size of what is produced locally.

Asymmetric Trade Flows

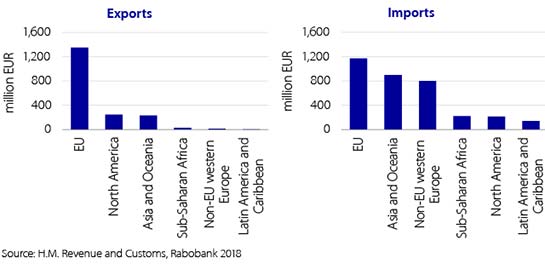

Currently, 70% of the UK’s finfish and shellfish exports are shipped to the EU (see figure), while British seafood imports come from more diverse sources. The EU supplies more than 30% of the UK’s seafood imports. Another 20% of UK seafood imports come from other non-EU Western European countries with which the EU has a preferential trade agreement, such as the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Norway.

The UK’s key seafood exports, namely, salmon, scallops, langoustine, mackerel, shrimp and prawns are largely exported to the EU member states. Of these species, only salmon has a significant market outside the EU, with around 17% of production being exported to the USA. Salmon, followed by cod, also has the highest value in British seafood imports. Both species are largely supplied from non-EU Western European countries and the EU.

Introducing tariffs on seafood trade flows between the isles and the mainland would hamper UK seafood trade more than EU seafood trade. If tariffs make the UK uncompetitive in exporting to the EU, Britain might have difficulties in finding new export markets for its seafood products, while the damage of tariff imposition on the EU would be more limited, as the EU can divert its seafood exports to other regions more easily. Moreover, British seafood imports would become more expensive if the UK doesn’t sign a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU and other non-EU Western European countries.

The EU and the UK agreed on a Brexit transition agreement on March 19, 2018, which is expected to ensure free trade until December 31, 2020. However, the transition agreement is not yet legally binding. Although Rabobank expects a transition period through to the end of 2020, followed by a free trade agreement, a hard Brexit still remains possible. In the case of an FTA, the terms of future trade will be subject to negotiations. Some seafood products might still be subject to tariffs under a free trade agreement, as preferential agreements could have exemptions for certain items, or some products could still be protected by tariff quotas.

Tariffs as High as 20%

In most trade negotiations, the starting point is the so-called Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) tariff rates, which are normal non-discriminatory tariffs established by the WTO. The EU’s MFN tariff rates that could apply to seafood products imported from the UK range from 2% to 20%. If tariffs were imposed, salmon trade flows would be least affected, as MFN tariffs on the EU’s Atlantic salmon imports are relatively low at 2%. If, on the other hand, the EU imposes MFN tariffs on other key British seafood export products such as scallops, langoustine, shrimp and prawns, this could hinder British exports to the EU considerably, as the EU’s MFN tariffs range from 8% to 20% on these species.

Currently, the UK benefits from tariff-free cod imports from the EU and other non-EU western European countries. Following Brexit, the future tariffs on British cod imports would depend on whether the UK signs FTAs with the EU and third countries. In case of a hard Brexit, tariffs would be defined by the UK under WTO rules. The EU’s MFN tariffs on cod imports range from 7.5% to 18%.

In order to maintain no or low-tariff seafood trade following Brexit, the UK might need to negotiate an FTA not only with the EU, but also with the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Norway. Tariffs are one factor adding “friction” to trade. However, with the introduction of borders, in a post-Brexit world, non-tariff barriers such as food safety measures and customs clearance procedures could also create friction for the EU-UK seafood trade.